The Queen Alexandra archives: Treating Island kids with artificial sunlight in the 20th century

This story is part of a new content series that celebrates the legacy of the Queen Alexandra Centre for Children’s Health, paying tribute to the origins of Children’s Health Foundation of Vancouver Island and the work we do today.

Decades ago, being prescribed sunshine by a health professional wasn’t unusual. Particularly between the late 19th century and into the 1930s and ‘40s, ultraviolet therapy was used to treat a variety of health conditions including circulatory diseases, heart conditions, and even polio.

By the time the Queen Alexandra Solarium For Crippled Children (which would later become the Queen Alexandra Centre for Children’s Health) welcomed its first patient in 1927, light therapy was a popular form of treatment for individuals of all ages. In fact, as stated in the Solarium’s earliest annual impact reports, Solarium means ‘a place in the sun’ and the centre itself was envisioned to be a ‘place where children needing long care, sunshine, and fresh air could be treated under medical supervision.’

Sunshine was essential to the well-being of the Solarium’s earliest patients, something that is highlighted by the building’s design and by donations. On the southwest corner of the building is the enclosed veranda with a large bay window to let in natural light. A new UV lamp was donated in 1938 (same year that a hydrotherapy tank and two stationary bicycles were donated by the Venture Club), and by the mid-1940s, the Solarium was providing 20 to 30 ultraviolet treatments per day to its young patients.

And based on the cheery notes from parents and Solarium alumni, fun activities planned to pass the time, and the smiling faces in historical photos, the Solarium itself was a cheery, sunny place for medical practitioners and patients alike!

From the Queen Alexandra archives:

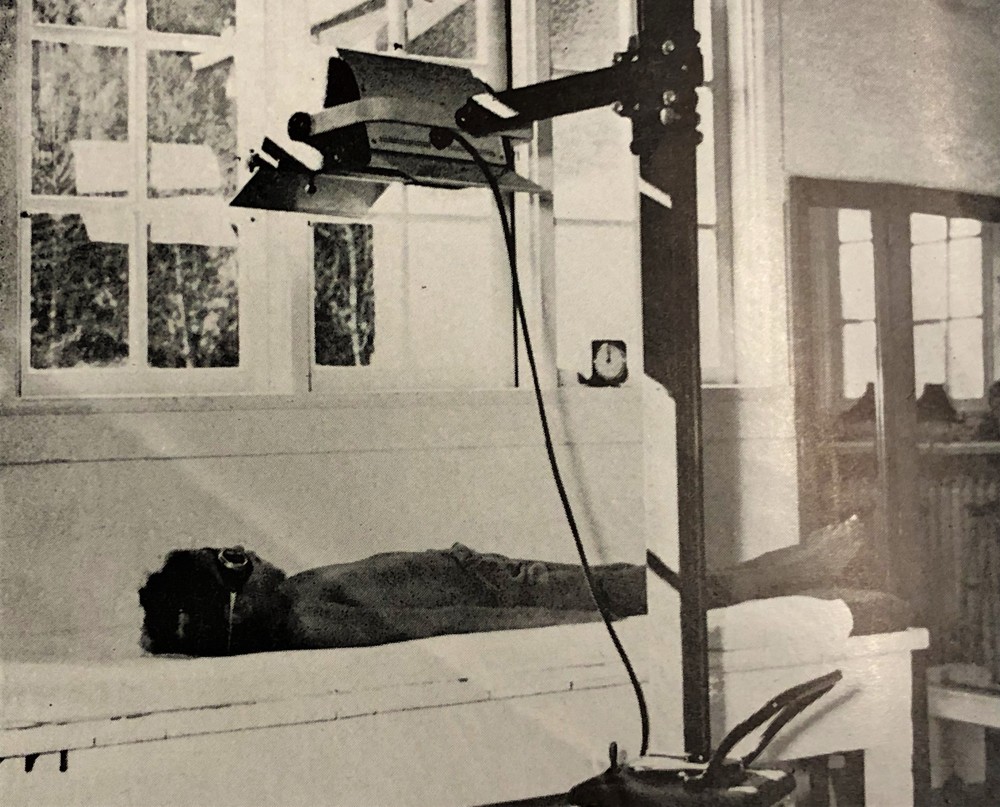

This photo was taken in 1931 and shows children, under the careful watch of Nurse Karen Gibb, at the Solarium about to undergo ultraviolet treatment. They’re ready for the treatment, wearing protective goggles.

This form of treatment was still used at the Solarium into the 1940s. In fact, in 1946, the Thetis Club of Vancouver donated a new UV treatment unit to the Solarium. According to the Queen Alexandra Solarium For Crippled Children’s 1946 annual impact report, it was the most modern unit of its kind available at that time and was ‘effective synthetic sunshine.’

Two Solarium patients, Betty Lou and June, pictured in 1945, sitting on the veranda and doing a puzzle, soaking in the natural UV light streaming in from the big bay windows.

Protective goggles worn by children who were patients at the Solarium are kept as artifacts in the Queen Alexandra Centre for Children’s Health archives.